Interview

Whatever Happened to Victor?

Brian Anthony Interview by Ed Watz

The novel Victor's Big Score was made into a feature film in 1992. It received enthusiastic reviews and was an award-winner at the Huston International Film Festival. Despite this, Victor's distibutor decided not to release the film and other than sporadic viewings, Victor has not been seen in decades. The following interview with filmmaker Brian Anthony chronicles some of the highs and lows of this independent production.

EW: Victor's Big Score was your first film?

BA: It was my first feature film. I had made about forty short films in the previous ten years, just for the fun and experience. Some were shot in a single afternoon, others over a period of months. Sing a Sad Song (1978) took over a year.

EW: What kind of a movie can you shoot in an afternoon?

BA: Short films, really short films. Most ran a minute or two. They were all comedies: Spindle Safety, Abe Lincoln Gets Head, Gopher Broke, Nature Boys make the Scene, Erectico, Cowboy Out, The Broken Spur and others. While shooting one film we threw a dummy out a window and filmed it six times from six different angles. We liked all the takes, so the next five films ended with a dummy flying out a window.

EW: What did you do with these films?

BA: Some are lost but I still have a number of them. My partner, Bill Walker, and I called our films “Lowtide Pictures,” and a few years ago we cleaned up and telecined about twenty-five titles. We burned it to DVD and called it The Very Best of What's Left of Lowtide Pictures.

EW: How did you jump from shorts to a feature film?

BA: I didn't. I worked in the film department at Emerson College for ten years, and also freelanced as a cinematographer, sound recordist and editor, mostly on commercials and industrials. I worked at an animation studio for three years, and wrote constantly. My first feature script was Beatnik Hangout (1979), which was written for Victor Buono. I couldn't raise the budget, and when Buono died I burned the script.

EW: So how did you go about making a feature?

BA: Back in the 80s a friend of mine was working at a studio in Hollywood. He found a book, Victor's Big Score, in a garbage can—it had been discarded by the Submissions Department. He sent it to me with a note that said: “You should make this into a film.” It was a great story, and that started it all.

EW: Okay, but making a feature is a huge endeavor. How did you start?

BA: First I optioned the book from the author, John Hill. John wrote a story about a barber, Victor, who tries to marry an old lady for her money. John was actually a barber, and the story had some very autobiographical elements. After paying my lawyer to draft an agreement, I didn't have the two thousand dollars to pay Hill for the option. When I walked over to my car that night, I found a forty-foot tree that had been cut down had crushed my car. So I used the insurance money to pay for the option.

EW: Then what did you drive?

BA: I just put a car-jack on the floorboards in the back seat, and un-crushed the car. The whole top just sort of pushed up and unbent. I had to replace the windows and it never looked right, but it drove okay.

EW: How did you raise the film's budget?

BA: First I wrote the script, which took a few months. It was much tighter and a better selling tool than the book. Then I sold my stuff. I was a big fan of underground comic book art and bought some original art before prices skyrocketed. I sold a Robert Crumb page from ZAP #1 for four thousand dollars—imagine what it's worth today! Over a period of three years I put together five investors, one of whom put up the lion's share of the budget; but that's five out of several hundred people I pitched it to. We finally raised the two hundred thousand dollars to go into production.

EW: Where did you go from there?

BA: Script, budget, schedule, casting, locations, equipment, crew, legal clearances... I worked for three years with a producer, Michael Bartell, who unfortunately wasn't available during the actual shoot. Phyllis Diller was going to play the old lady. I met with her and she was really enthusiastic, and would have been perfect. But SAG came down on us like a bag full of hammers, so we had to cast it all non-union. It was a tough shoot, July and August of 1990, with temperatures in the upper 90's. And since it supposedly took place on Halloween, the actors were bundled in heavy jackets! We used twelve large bags of leaves, which we had raked up the previous fall. They were spread over the green lawns on location shoots, and carefully raked up and bagged for the next location. We freeze-dried some pumpkins but they didn't last; the ones in the film were sculpted in clay and painted.

EW: Did you shoot exclusively on locations to save money?

BA: No, studio shooting actually proved less expensive. No permits, honey wagons, generators, rubbernecks or police details. And no rain. It's a matter of control. Most of the interiors were shot in a 150 year-old warehouse in East Boston. The head set designer and chief builder was a fireman with the Boston Fire Department, he helped us with the hurricane scenes. The fire department turned out with hoses to simulate a hurricane! So we really tried to use all of the resources around us.

EW: What about the car that goes in the water?

BA: The Amphicar. It was an amphibious car built in the 1960's. It's not a very good car or a very good boat, but it is both. In the story Victor borrows money from the old lady and buys a car. I was in California the previous summer and a friend had an amphicar. I thought it would be a great prop, and suggested lots of visual gags. But they're west coast cars and not common in Boston. At a pre-production meeting I was telling Eran Loebl, the production manager, what I wanted. He was staring out the window, looking a bit distracted. I finally asked “Eran, can you find me an Amphicar, a red one?” He just pointed out the window and said “How about that one?” And parked right on the street was a red Amphicar! We waited for the owner to show up and he was very nice about it. So we got our Amphicar.

EW: There are some very funny animated shots in the movie.

BA: The hurricane sequence was inspired by Buster Keaton's “Steamboat Bill Jr.” People are running and driving around, hanging out of windows on ropes, all in the middle of a hurricane. We couldn't go big with live action mechanical gags, so we animated some scenes. Mark Frizzel, a talented animator, shot a scene where a van is crushed by a tree. We shot a rain matte, just backlit water against a black background, and superimposed it over the animated shot. It worked so well that when I needed a shot later in the story, of the crushed van disappearing over a hill into the sunset, Mark animated that too. And we did a mechanical gag using a miniature Amphicar, crossing the Charles River in the middle of the raging storm.

EW: Did you shoot in 35mm?

BA: We shot in Super-16, which has the same aspect-ratio as 35mm, then blew it up to 35mm. We did some tests and found the most critical factors were not just lenses, stock and lighting, which you might expect, but set design. We wanted a saturated Technicolor look, which worked well with the requirements for blow-up. We finished principal shooting in 28 very long days.

EW: Did you do any additional shooting?

BA: There were five days of pick-ups. I was working with Loren Miller, a talented film editor who was doing our sound editing, and he called me one day. “We're getting a real hurricane!” So he picked me up and we drove through the storm, grabbed a Bolex camera and a hundred feet of negative film, and scaled the highest building over Beacon Street to shoot some rain scenes. I had my feet planted in the openings of two cinder blocks so I wouldn't blow away. We scurried out of there before the police arrested us for trespassing, running for Loren's 280-Z—and it was gone. His car was stolen in the middle of the hurricane!

EW: So what happened to the film?

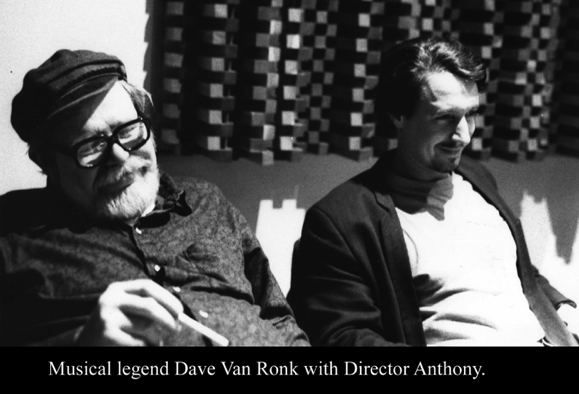

BA: First we tried to promote interest. Dave Van Ronk, the folksinger, sang and performed a song written for the film by John Voci, “Victor's Big Song.” And S. Clay Wilson, the cartoonist, did poster art and two wonderful lobby cards. But this gave people the impression it was an animated film, so we had to make up some scene cards too. Victor's Big Score premiered at the Coolidge Corner Theater in Brookline and played for two weeks, so we could garner some reviews.

EW: What was the critical reaction?

BA: Variety liked it a lot, and so did some other critics. But some reviews were really hostile. One reviewer said “There's something distasteful about a man trying to marry an old lady for her money...” I think she missed the point. The hurricane is God trying to trip up Victor, it's a karmic monkey-wrench. But some of the critic didn't see it that way.

EW: Then you went the festival route?

BA: Just one, the “Houston International Film Festival.” It was a packed audience, mostly cowboys, and they were really digging it, laughing and hooting! The best audience reaction the film ever had!

EW: And how did you get a distributor?

BA: We sent screeners and press kits to everyone, got turned down by all the majors, and finally made a deal with a smaller but well-known distributor. They were supposed to sell theatrical and ancillary markets worldwide, by territory. I didn't really expect theatrical sales, but thought we would do well in cable and video. Then we were going to four-wall it in a theater domestically.

EW: What was your goal?

BA: To make enough money to finance another film.

EW: But the distributor never distributed it?

BA: No, they made up these great sell-sheets, which looked like mini one-sheets. But then they had a major turnover in personnel, and the new sales rep buried Victor then and there. After over two years I asked to be let out of the contract. The distributor returned the box of screeners I had sent them, 100 tapes, and it had never even been opened. They never sent out one screener.

EW: Then what happened?

BA: I finally realized that it just wasn't going to happen, and I didn't want to spend any more years of my life on a long-finished project. I moved on, came out to California, and ended up writing and producing some shows. My co-author, Bill Walker, and I write and publish one or two books a year.

EW: How do you feel about the way things turned out?

BA: I try to be philosophical. There's a line in the movie: “You don't get what you deserve. You get what you get.” And that's it. I had plenty of luck getting the film made, but luck has a way of changing.

ADDENDUM

by Brian Anthony

When the distributor decided against releasing Victor they continued to legally control the rights, and the film was unavailable to me. I moved to California, worked in production for a decade, and eventually left production to start my own art restoration business.

The desire to write never left me, and I co-authored several screenplays with my great friend from my college days, Bill Walker. In addition to screenplays Bill was an accomplished novelist, with several books to his credit. Some years ago Bill asked me if I wanted to try collaborating on a book, and to date we have written seven books together.

In the summer of 2018 Bill inquired what had happened to Victor, and I explained the 35mm positive prints, original negative, and sound mixes were all in storage. He suggested we gather the material, assess its condition, and consider transferring it to a high definition digital format.

Just as in the old days we began calling in favors, cutting deals, and working with friends. It was exhausting, frustrating, and exhilarating--as independent production always is.

Loren Miller is an editor in the Boston area and had done the sound editing on Victor almost thirty years ago. We remained friends and when apprised of our plans he jumped on board wholeheartedly. Loren dust-busted the entire transferred film, and made timing and color corrections. We then examined some sequences in the film I was never entirely satisfied with, trimmed a couple of scenes, transposed two shots, and even added one image.

The film sound element was a 35mm mono optical negative. We went back to the original 35mm mag mix and transferred all of the individual tracks, which not only provided much better fidelity, but allowed us to create a brand new stereo mix.

The 4K restoration of Victor looks better than I thought possible, and after a quarter of a century my film is finally getting the distribution I had hoped for.

So maybe Victor's long, strange journey is fated for a happy ending after all.

--Brian Anthony

Social